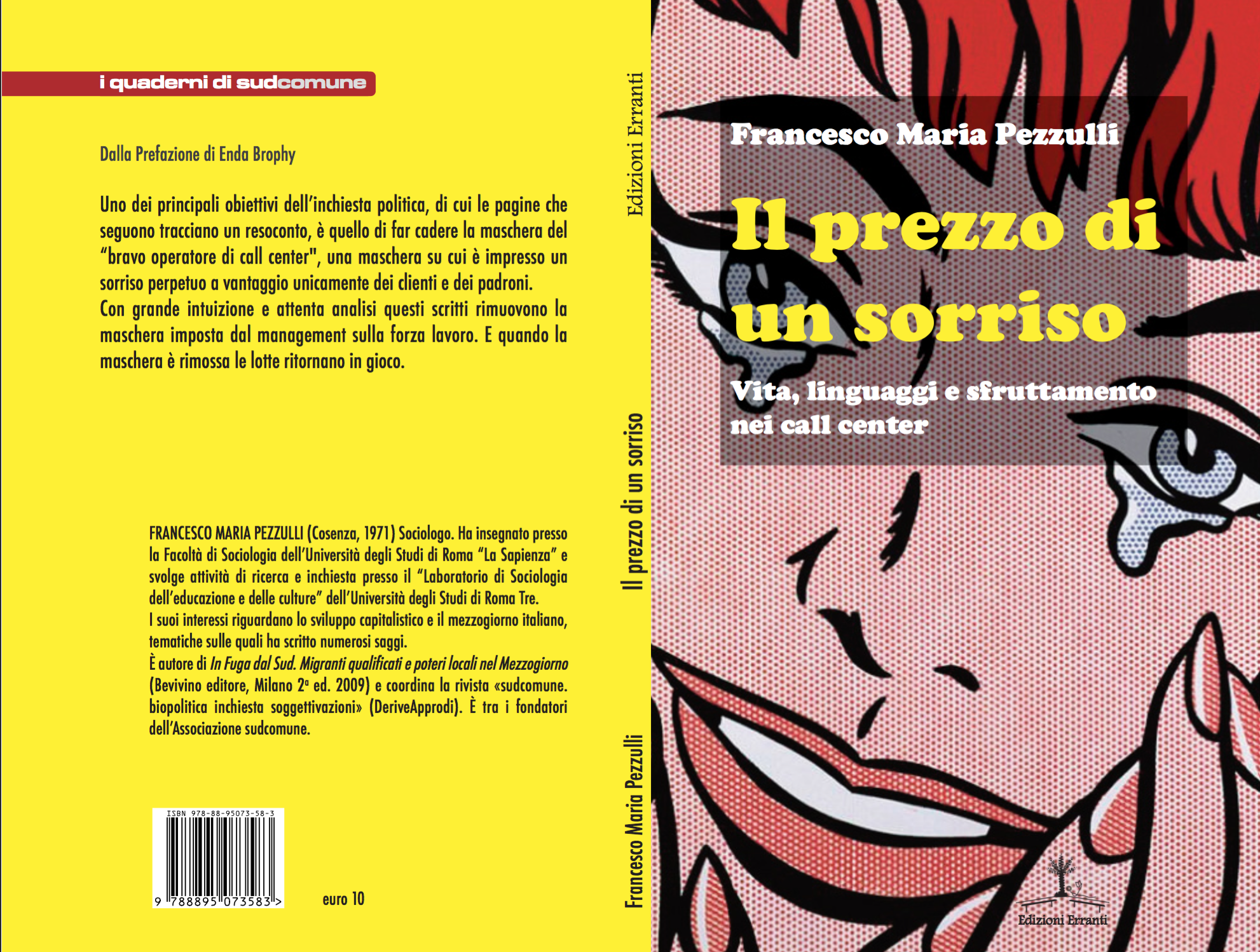

Prefazione di ENDA BROPHY al Quaderno di sudcomune (n.1/2017) “Il prezzo di un sorriso. Vita, linguaggi e sfruttamento nei call center”

Al crepuscolo del fordismo, nel 1970, il famoso sociologo americano Daniel Bell divise la storia umana e le sue forme predominanti di lavoro in tre fasi. In epoca preindustriale, Bell suggerì, gli esseri umani sono stati impegnati principalmente in un gioco contro la natura. Nell’epoca industriale i lavoratori sono stati impegnati in una partita contro le macchine. Nell’epoca post industriale, che il professore di Harvard vide emergere, invece, osservò che il lavoro usciva dalla fabbrica per diventare un «gioco tra persone». L’argomento e le sue implicazioni saranno familiari a molti. Da Bell in poi successive generazioni di teorici liberal-democratici e di management del lavoro hanno interpretato il “knowledge worker” come portatore di un futuro migliore: oltre la fatica della fabbrica, oltre l’alienazione e le gerarchie cui è stato sottoposto il lavoro fordista. La grande narrazione di Bell è anche un ammonimento sui pericoli dell’analisi accademica distolta (The coming of post-industrial society: A venture in social forecasting, Basic Books, New York 1973).

I racconti senza compromessi contenuti in questi Quaderni sul lavoro nei call center calabresi, l’attenta analisi dello sfruttamento e della resistenza quotidiana che offrono, ci trasmettono invece una immagine profondamente diversa a partire delle forme di lavoro di più rapida crescita dell’ultimo quarto di secolo. Per dirla con una preziosa formulazione contenuta in un intervento, le testimonianze offerte nelle pagine che seguono ci narrano di «nuovi soggetti e vecchie modalità di sfruttamento», che continuano però ad animare un settore assolutamente vitale per il capitalismo contemporaneo.

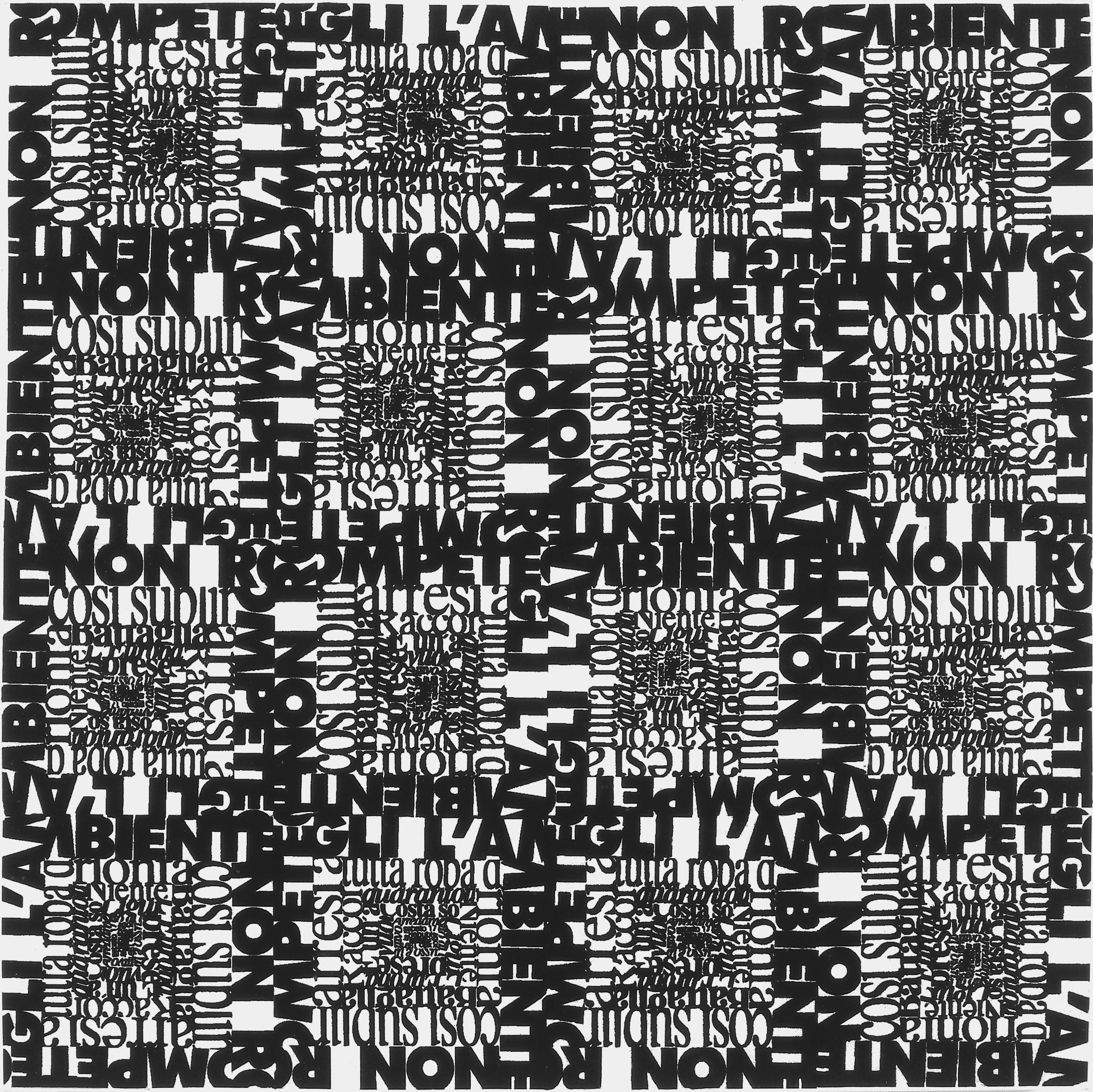

L’indagine svolta da questi ricercatori militanti ci dà una prospettiva graffiante su come la fabbrica del «gioco tra le persone» e la sua produzione di una forza lavoro sorridente, piena di comprensione e amichevole, viene effettuata a costo di salari da fame, di esaurimento emotivo, di ansia insopportabile e depressione diffusa. Dagli anni novanta i call center proliferano in tandem con la crescente comunicatività del capitale. Per la maggior parte delle grandi aziende oggi c’è l’aspettativa che i consumatori possano mettersi o restare in contatto con loro, personalizzare il servizio, ottenere aiuto per l’utilizzo del prodotto, controllare lo stato del proprio account, notificare la compagnia quando ci sono problemi, offrire un commento, minacciare di rompere il contratto, e così via. In attività anche molto diverse come fornire supporto tecnico, propagare truffe online, promuovere candidati politici, ricercare modelli di consumo, dispensare consigli sulla salute, pubblicizzare nuovi prodotti; ed anche per individuarci e “rimettere a noi i nostri debiti”, i call center sono diventati un apparato di vitale importanza per la mediazione del rapporto tra le istituzioni e i soggetti del capitalismo digitale in quello che alcuni hanno definito « un cambiamento paradigmatico nelle modalità di interfacciarsi con i clienti che attraversa l’intera economia» (Bain, Taylor, Watson, Mulvey, e Gall, “Taylorism, targets and the pursuit of quantity and quality by call centre management”, in New Technology, Work and Employment, 17(3), 2002, p. 184). Attraverso milioni di transazioni al giorno, i call center intessono rapporti tra istituzioni e consumatori attraverso le infrastrutture di telecomunicazione dell’economia globale. Il risultante flusso continuo di comunicazioni deve essere organizzato e compresso in modo che costi al capitale il meno possibile, e lo sviluppo dei call center nel corso degli ultimi decenni del ventesimo secolo rappresenta la risposta a questa nuova necessità, la sua razionalizzazione, la sua dimora nascosta nella produzione comunicativa. La raccolta di esperienze nei call center presentate in questo quaderno chiarifica quanto la nuova forza lavoro sia collegata alla accresciute esigenze comunicative del capitalismo. Bell aveva assolutamente ragione quando notava l’emergere di un regime di accumulazione in cui il linguaggio, gli affetti e la comunicazione diventavano sempre più fonte di valorizzazione. Quello che convenientemente ignorava era la possibilità che una versione digitalizzata dell’organizzazione scientifica del lavoro di stampo taylorista diventasse un mezzo efficiente (anche se non sempre efficace) per generare plusvalore comunicativo dai lavoratori cognitivi. I call center, come i testi che seguono illustrano in modo vivace, impongono agli operatori, dall’alto, delle forme di comunicazione intensamente strumentalizzate, attraverso script progettati per dividere consumatori ingenui dal loro denaro, vendere loro qualcosa di cui non hanno bisogno, o far finire la conversazione molto più velocemente di quanto succederebbe in circostanze normali. Il call center nega la comunicazione, ma dipende anche da essa. Se le tecniche razionalizzate per l’estrazione di plusvalore sono purtroppo familiari per chi ha conosciuto e conosce la fabbrica, ciò che l’inchiesta politica conferma è che nei call center si verifica una forma di accumulazione “bio-economica”, che valorizza le capacità sociali sviluppate al di fuori del posto di lavoro. Questi interventi esplorano il contenuto sociale del dialogo-merce, notando con attenzione la diversità delle prestazioni, delle forme di misura e dei metodi di controllo della forza lavoro all’interno della galassia dei call center. Allo stesso tempo, anche con tutta la diversità nelle applicazioni di questo assemblaggio, ciò che rimane costante è la valorizzazione da parte del capitale dei sorrisi della sua forza lavoro, l’appropriazione che esso compie della totalità della loro socialità. Sulla linea di montaggio nella fabbrica tradizionale la mente poteva almeno vagare mentre il corpo faticava. Con una catena di montaggio linguistica, invece, il lavoro invade la soggettività e con essa quello che resta del tempo libero, come ben evidenzia il tic consueto (ripetere gli script) che hanno gli operatori anche quando rispondono al telefono ad amici. Questi testi rivelano anche, semmai dovessero esserci ancora dubbi in proposito, l’incredibile potenziale dell’inchiesta militante applicata alle questioni del lavoro. Come tale, l’inchiesta al centro di queste analisi ha molto in comune con le indagini illuminanti sui call center condotte in Europa, America Latina e Asia del Sud da reti di lavoratori, attivisti, sindacalisti e dai loro alleati nelle università. Collettivi come «Colectivo Situaciones», la “Cátedra Experimental Sobre Producción de Subjetividad”, “Kolinko”, “Gurgaon Workers News” e altri hanno affinato un metodo lanciato da Marx e raccolto dagli operaisti italiani, un metodo che attraversa la composizione della forza lavoro e la loro soggettività, tenendo sempre in primo piano la possibilità di costruzione di organizzazioni collettive e di lotta. L’immagine spietata, senza veli, del settore globale dei call center che emerge da questi studi è la risposta più efficace agli scritti autoreferenziali dei teorici di management americani. Il sapere più prezioso per il proletariato digitale è quello prodotto in maniera immanente, dalla rabbia per le umiliazioni subite in questo posto di lavoro loquace. È all’interno delle “situazioni insostenibili” che si vengono a creare che l’organizzazione aziendale mostra per intero le sue lacune e il suo carattere ideologico; ed è in queste situazioni che le forme di soggettività imposte dal management sulla forza lavoro, spesso riluttante, vengono percepite come ambigue e contraddittorie. Uno dei principali obiettivi dell’inchiesta politica, di cui le pagine che seguono tracciano un resoconto, è quello di far cadere la maschera del “bravo operatore di call center”, una maschera su cui è impresso un sorriso perpetuo a vantaggio unicamente dei clienti e dei padroni. Con grande intuizione e 13 attenta analisi questi scritti rimuovono la maschera imposta da management sulla forza lavoro. E quando la maschera è rimossa le lotte ritornano in gioco.

§§§§§§§§§§§§

Unmasking Call Centre Work

Enda Brophy

At the twilight of Fordism in the 1970s, the renowned American sociologist Daniel Bell divided human history and its predominant forms of labour into three stages. In the pre-industrial era, Bell suggested, humans were primarily engaged in a game against nature. In the industrial era workers were in the throes of a game against machines. In the postindustrial era he saw emerging, the Harvard professor observed, labour would exit the factory to become a game between people. The argument and its implications will be familiar to many. Since Bell, successive generations of liberal-democratic and managerial theories of the contemporary workplace have seen the “knowledge worker” as the purveyor of a better future, free of the drudgery of the factory, the alienation of labour, and the hierarchies of the Fordist workplace.

Bell’s grand narrative is also a cautionary tale about the dangers of detached academic analysis. The uncompromising accounts of work experience in Calabrian call centres contained in this collection, the careful analyses of quotidian exploitation and resistance they offer, tell us a very different story about one of the fastest-growing forms of employment of the last quarter century. To put it in their own, deeply valuable formulation, the testimony offered in the pages that follow tell us of the “new subjects and old modes of exploitation” currently animating an industry which has become absolutely vital to contemporary global capitalism. The inquiry carried out by these researchers gives us a scathing take on how the “game among people” that is call centre work and its production of an unflinchingly smiling, understanding, and friendly series of laboring performances comes at the cost of poverty wages, emotional exhaustion, insufferable anxiety, and widespread depression.

Since the 1990s call centres have proliferated in tandem with the growing communicativity of capitalism. For most large companies today there is the expectation that consumers will be offered the opportunity to get or keep in touch, customize their deal, get help using the product, check the status of their account, report failures, offer feedback, threaten to break their contract, and so on. In activities as diverse as providing tech support, proffering scams, promoting political candidates, surveying consumption patterns, dispensing health advice, pitching new products, or haranguing us to pay back our debts, call centres have become a vital apparatus for mediating the relationship between the institutions and the subjects of digital capitalism in what some have called a “paradigmatic shift in the ordering of the customer inter-face across the entire economy” (Bain, Taylor, Watson, Mulvey, & Gall, 2002, p. 184). Through millions of transactions a day, call centres knit together relations between institutions and consumers across the information relays of the global economy. The resulting ceaseless flow of communication must be organized and compressed so as to ensure it costs capital as little as possible, and the birth of the call centre during the last decades of the twentieth century represents capital’s dominant response to this necessity, its rationalization of these functions, its hidden abode of communicative production.

The collection of accounts gathered here illuminates the new workforce attached to capitalism’s expanding communicative requirements. Bell was entirely right, of course, to note the emergence of a regime of accumulation in which language, affect and communication were increasingly becoming a source of valourization. What he conveniently ignored was the degree to which a digitized version of Taylorist scientific management would become a highly efficient (although not always effective) means for generating a communicative surplus from workers. What the call centre gives us, as these accounts illustrate so vividly, is the imposition on workers of intensely instrumentalized forms of communication from above, through scripts intended to part gullible consumers from their money, sell them something they don’t need, or end the conversation much faster than it would under any other circumstances.

The call centre negates communication, but it also depends on it. If the rationalized techniques for surplus value extraction in this workspace are painfully familiar, what this process of co-research in Calabria confirms is the degree to which this form of employment, as the authors suggest, is a “bio-economic” form of labour, which puts to work all sorts of social capacities developed outside the workplace. These essays explore the social content of conversation that is bought and sold, carefully noting the diversity of performances, forms of measure, and methods for labour control that exist within the call centre galaxy. At the same time, for all of the diversity of these situations, what remains consistent is capital’s valourization of its workforce’s smiles, its appropriation of the entirety of their sociality. At least on the physical assembly line one’s mind could wander off while the body toiled. With an assembly line in the head the work invades what remains of leisure time, causing workers to answer a call from friends using the scripted communication they are forced to emit during the waged portions of their day.

These pieces also reveal, once more should there be any question, the vast potential of militant inquiry in the investigation of labour. As such the inquiry at the heart of this collection has much in common with the illuminating inquiries into call centre work produced in Europe, Latin America, and South Asia by networks of workers, labour activists, trade unionists, and their academic allies. Collectives such as Colectivo Situaciones, the Cátedra Experimental Sobre Producción de Subjetividad, Kolinko, Gurgaon Workers News, and others have similarly honed a method that traverses workplace composition and subjectivities with a view to building collective organization and social struggle. The unforgiving view of the global call centre industry that has emerged from these studies and the perspective of its workforce is the most effective response to the self-satisfied writings of American management theorists. The knowledge that is most valuable to the digital proletariat is that which is produced immanently, out of the rage at the indignities suffered in this loquacious workplace.

It’s within these “unsustainable situations”, as the collection calls them, that gaps can be found in the models of subjectivity produced and imposed by management on an often unwilling workforce. One of the main goals of political inquiry, one of these entries suggests, is to “take the mask off” the “good call centre worker,” a mask upon which there is imprinted a perpetual smile for the benefit of customers and management. With great insight and careful analysis, these writings remove that mask imposed by management on labour. And, once that mask is off, anything can happen.